Simply meeting a positive annual energy balance is not enough to ensure optimal environmental performance or efficient building operations. For instance, a Plus Energy Building (PEB) might generate more energy than it consumes over the year, but if energy production does not align with consumption patterns, it could result in exporting a high share of the overall renewable energy production and a need to purchase more expensive peak demand energy. This means losses for bill payers and more stress on the energy grid.

This scenario highlights the importance of carefully sizing and integrating energy systems to optimize energy generation, storage, and consumption. An optimized design ensures that renewable energy systems are scaled appropriately, maximizing both environmental benefits and economic performance within the framework of PEB standards. In this context building flexibility becomes a vital strategy.

What are flexible buildings?

Flexible buildings can adapt their energy consumption and production in response to external factors, such as fluctuating energy prices, grid demand, or the availability of renewable energy. This adaptability involves:

- intelligently shifting or reducing energy use,

- efficiently storing energy,

- managing on-site generation to support grid stability and minimize operational costs.

Importantly, this dynamic approach ensures that occupant comfort and building functionality are never compromised.

How can Plus Energy Buildings achieve energy flexibility?

To offer flexibility, PEBs must balance several aspects:

- Optimize insulation and how heat is retained and released.

- Ensure energy strategies don’t compromise living conditions and user comfort.

- Use technologies like heat pumps and PV to adapt energy use and production.

To evaluate building flexibility, four indicators are used:

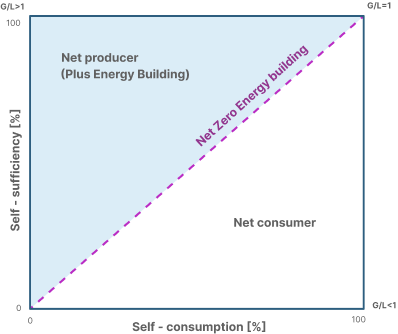

- Self-Sufficiency or Self-Generation (%): Percentage of the energy demand covered by renewable energy production. It is calculated as the ratio between the self-consumed generated energy (from PV to the building) and the total annual electric energy use.

- Self-Consumption (%): Percentage of generated energy which supplies local loads. It is calculated as the ratio between the self-consumed generated energy (from PV to the building) and the total renewable energy generation (energy generated from the PV system).

- Peak Export: The highest energy sent to the grid over a year.

- Peak Import: The highest energy taken from the grid over a year.

Strategies for flexibility in different climates

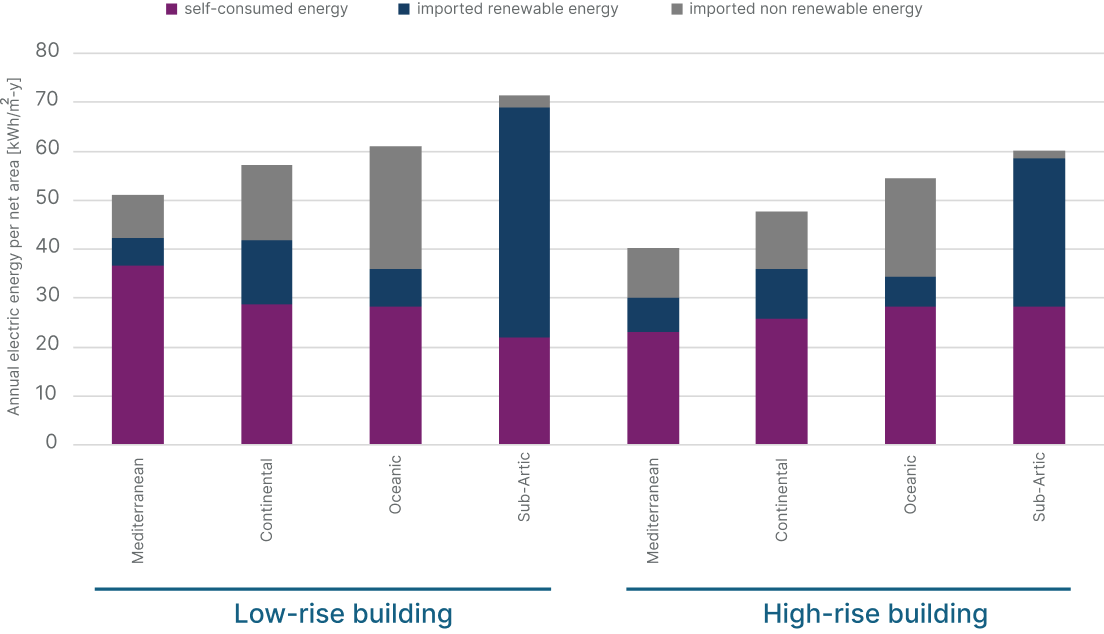

PEBs can significantly ease the strain on energy grids. Simulations of low-rise and high-rise residential buildings show that in Mediterranean climates, PEBs can achieve self-sufficiency rates of up to 70%. In other climates, self-sufficiency is over 40%, except for subarctic regions, where achieving these levels is more challenging.

In the Mediterranean, energy demand peaks during summer due to cooling needs. This aligns with the highest solar energy production, creating a great opportunity for buildings to use the energy they generate that is for self-consumption. However, in winter and transitional seasons, lower solar production and reduced cooling needs mean buildings may still rely on electricity from the grid. Batteries and smart energy controls can help store excess solar energy in summer for use later.

Strategies for flexibility in the Mediterranean climates could include:

- Smart control of solar panels and battery systems reduces energy costs by shifting energy use to sunny periods or times of lower electricity prices.

- Advanced controls can cut energy imports during high-price hours by 10%-13%.

- Adding smart electric vehicle chargers improves flexibility by storing and using renewable energy efficiently.

In sub-arctic climates, that is regions with long winters and limited solar potential, there’s often a gap between energy demand and production. To reduce this mismatch several strategies can be adopted:

- Increase building efficiency with high-performance insulation and energy-efficient heating to reduce energy demand.

- Install geothermal heat pumps that can further close the gap between production and consumption.

- Plan for overproduction by generating more energy in summer as it helps compensate for higher winter demand.

One example of flexibility in sub-arctic climates comes from Norway, where electricity prices change throughout the day. This creates unique challenges and opportunities:

- Night temperature setback: lowering indoor temperatures at night saves energy but shifts demand to the morning, when prices are high.

- Overheating at night: pre-heating when electricity is cheaper may reduce costs but must account for preferences like cooler sleeping temperatures.

If you want to know more about strategies for flexibility, have a look at the this study on building flexibility.

Advanced building performance optimization

Buildings can be made more energy-efficient with advanced control systems that optimize how energy is generated, stored, and used. With basic control we mean operations on the building’s heating, cooling, and hot water needs while minimizing thermal load. Advanced controls go a step further by coordinating the heat pump, solar panels, thermal storage, and battery systems. This reduces reliance on grid electricity and increases self-sufficiency by shifting energy use to times when solar production is highest.

For example, advanced controls adjust the thermal storage temperature and indoor setpoints to store energy during midday when solar power is abundant and the energy needs can be covered by photovoltaics. Predictive models based on weather forecasts help to know whether solar production will meet energy needs for the next day.

Strategies for optimization include:

- Increasing the size of thermal storage (e.g., tripling its standard capacity) allows more energy to be stored for later use, reducing grid reliance. However, this increases costs and space requirements. Adjusting storage setpoints during peak solar production maximizes solar energy use but may reduce heat pump efficiency, so it must be carefully managed.

- Heating loads can be shifted to midday solar peaks by slightly raising indoor temperatures, improving heat pump performance and reducing grid electricity use. This is especially effective during winter when heating demand is high.

- Space cooling aligns naturally with peak solar production. Instead of shifting loads, small temperature adjustments during high solar output and using ceiling fans can improve comfort with minimal energy use.

- Adding larger batteries (up to 20% bigger) helps store excess solar energy during seasons with lower thermal demand, like spring and autumn. In winter, achieving full solar coverage may require installing additional solar panels outside the building, which may not always be practical.

- Placing air-to-water heat pump units in shaded but well-ventilated spots improves efficiency, especially in winter, and prevents performance losses in summer.

For more detailed information on advanced building performance optimization, head over to the Report on multi-system control strategies for HMS from Cultural-E.

Except where otherwise noted, content on this page is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.